My references to the writings of other people–both indigenous and non-indigenous–do not in any way imply that they share my views on this matter. The opinions expressed here are my own and do not necessarily represent those of my family, friends or associates.

Part Four – A Introduction to Jay Peterson’s Involvement With Indigenous Issues, 1958 to 1976

In April 2011, I launched not only this blog about me generally, but also my counterpoise.ca (counterpoise2.blogspot.com) which covers my views on indigenous issues. Some of my counterpoise.ca posts mention my mother, e.g., the fact that she was the main reason I got connected with the aboriginal “cause.” However, until now, I have said very little on my leithpeterson.ca site about her work in this area.

Part of the reason for this is my views on this topic have diverged substantially from my mother’s over the course of the 40 years she has been gone. In fact, I have become so disillusioned with many aspects of the “cause,” that, since about the mid-2000s, I have primarily been on the outside looking in. There are a few aboriginals who I keep in touch with, who share at least some of my views, but for the most part, I keep my distance from the whole scene. For further information about my opinions on this, you can check out my counterpoise.ca blog.

In Part Four–Sections B to E below–I have tried to be as objective as I can about what my mother was doing at the time she was involved.

Part Four – B Indigenous Visitors to 283 Dufferin Avenue in London, Ontario, etc.

According to a biographical sketch my father put together around 1970, my mother “became interested in the plight of Indians* [in 1958] when she found a young teacher from Trinidad helping the Indians** without compensation on his summer vacation, and Canadians themselves not doing it.”

Mom frequently went to various aboriginal communities in the London, Ontario area–from Kettle Point to Cape Croker***–and visited with the native women. Often she would buy their crafts from them, sell the items in town, and then bring the money back to the women. What resulted was a lifelong friendship with natives on various reserves in Southwestern and Central Ontario and in the London area.

My father shared my mother’s enthusiasm for indigenous issues, particularly in connection with environmental stewardship. He told me that every year, for many years, he gave 5,000 saplings to both Oneida of the Thames and Six Nations–and planted some of them himself. One year, he said he gave 22,000 to Six Nations. No wonder his friends there called him the “tree man.” His funeral program included an “Iroquois prayer.”

I recall a number of aboriginals who paid visits to our home at 283 Dufferin Avenue In London, Ontario, Canada. They included people from Six Nations, Cape Croker***, Oneida and other communities. I have various materials that document my parents’ and my involvement during this period. These materials include guest book entries, correspondence, programs and news clippings.

Our family home was filled with aboriginal crafts, including Mohawk pottery and corn husk mats from Six Nations, plus sweetgrass baskets and silkscreen-printed cards from Cape Croker***.

|

| Jay Peterson in front of 283 Dufferin Avenue, London, Ontario, ca. 1967 |

Part Four – C Indian-Eskimo Association of Canada (IEA), ca. 1964-1973, and the Canadian Association in Support of the Native Peoples (CASNP), 1973-1976

My mother was active with the Indian-Eskimo Association of Canada (IEA) from about 1964 to 1973. G. Allan Clark, the Indian-Eskimo Association executive director, wrote a letter to my father, dated March 6, 1970, in which he extolled the many ways my mother supported the aboriginal cause. He said “Jay’s home” provided support and encouragement for indigenous people, much like the N’Amerind Friendship Centre in London.

Clark also talked about the exhibits she arranged at the Western Fair, to help educate the non-native population regarding native contributions to “Ontario’s history and culture.” I remember attending some of these Western Fair exhibits with my mother. As I recall, aboriginals from different communities, such as Cape Croker*** and Oneida of the Thames, demonstrated their skills, such as sewing intricate beadwork designs.

When the Indian-Eskimo Association (IEA) moved from Toronto to Ottawa in 1973, there was a name change to the Canadian Association in Support of the Native Peoples (CASNP). My mother continued her advocacy work under the CASNP moniker from 1973 until her passing in 1976.

The Fall 1978 CASNP Bulletin, entitled “On Native Women,” was dedicated to my mother. Joanne Hoople, the CASNP executive director, described my mother as a “selfless worker throughout her adult life. . .who is remembered as someone who inspired others.” Hoople talked about my mother’s contribution to the establishment of the N’Amerind Friendship Centre, as well as her work “furthering the objectives of the Indian-Eskimo Association” and then CASNP.

Part Four – D Interest in Indigenous Art and Symbolism

My mother’s B.A. in Art History from the University of Rochester (1941) and her B.A. in Occupational Therapy from the University of Toronto (1943) heightened her appreciation for those who were creative and artistic.

In addition, her 19th Century Scottish cotter ancestors had instilled in her a deep appreciation for folk art. In 1949, shortly after she moved to London, she wrote about the importance of folk art. She described it as the “art of the people,” which included many homecrafts, such as weaving, sculpture, toy making and woodcraft.

She said the Industrial Revolution had caused folk arts to die out, but that they should be revived. I think both her education and her interest in folk arts contributed substantially to her support for indigenous peoples’ artistic and creative abilities.

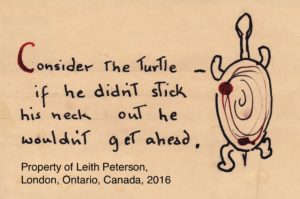

In addition, my mother was interested in symbolism in all its forms, so it is not surprising that she would be fascinated by the aboriginal version of this. For instance, she was intrigued by the Iroquois creation stories that include the “Turtle.”

I am not saying my mother’s turtle artwork below represents any indigenous story, but I think it is an example of how her connection with indigenous people heightened her appreciation for the natural world.

|

| Jay Peterson’s turtle artwork, ca. 1964-1974 |

Part Four – E Native (a.k.a. Indian) Studies Course Instructor at Fanshawe College, ca. 1970-1973

She taught Native (a.k.a. Indian) Studies at Fanshawe College, in London, Ontario, circa 1970-1973. I have copies of some of the material she helped prepare for this course, including a one-pager entitled “Ways of Wisdom.” Twenty-one aboriginals from different tribes across the country helped her assemble this document. It includes 11 observations, such as native people were more interested in “BEING than BECOMING.”

Some of the course content I have is unsigned and may have been written by others or in collaboration with others. Aboriginals who I am assuming were guest lecturers for the course also wrote some material that I found in her course files.

However, I know that “Ways of Wisdom” was written by her because I have her handwritten drafts.

Part Four – F My Comments About My Mother’s Involvement with Indigenous Issues

It was difficult for me to write about this topic because, as I said in the introduction to this post, my views on aboriginal issues have changed substantially from my mother’s over the past 40 years. Her experiences spanned an 18-year period, but mine have lasted more than 35 years.

Although I share her view that non-aboriginal people need to be better informed about the history and heritage of indigenous people, my approach is quite different from hers in other respects. For more information on my views, you can look at my counterpoise.ca blog.

Part Four – G Notes

* I realize that some indigenous people prefer that the term Indian not be used, but it was the word often employed at the time my father wrote his biographical sketch of my mother (circa 1970). In addition, Indian has a specific meaning under the terms of the Indian Act. See Gibson citation below for further information on this.

Moreover, many aboriginals still call themselves Indian and do not find the term offensive. See MacBain citation below.

Finally, no legal definition exists for First Nation, although many aboriginals prefer to refer to themselves this way. See my citation for the Government of Canada’s TCPS 2 (2014) – Chapter 9 below.

** My father was referring to the Trinidad teacher “helping the Indians” in two or more aboriginal communities southwest of London. These communities are now called Chippewas of the Thames, the Munsee Delaware Nation and the Oneida Nation of the Thames settlement. Note that the first two are reserves, but the latter is a settlement. For further information on the history and current situation of these communities, refer to the relevant websites listed below.

I found some of the content in the McCallum document (cited below) helpful for preparing the information on Southwestern Ontario aboriginals.

*** Cape Croker has a very complicated history which is beyond the scope of this post. For further information, please refer to the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation site, which is listed in the citations below.

Bibliography

Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation. Retrieved December 14, 2016 from: nawash.ca

Chippewas of the Thames. Retrieved December 11, 2016 from: cottfn.com

Gibson, G. (2009). A New Look at Canadian Indian Policy. Fraser Institute. Pages 18-29 discuss the fact that Indian has a specific meaning under the terms of the Indian Act.

Government of Canada (2015, July 7). TCPS 2 (2014) – Chapter 9 – Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Metis Peoples of Canada. Retrieved October 18, 2016 from the Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics (PRE): www.pre-ethics.gc.ca. On page 21, in endnote #1, there is a reference to there not being a legal definition for First Nation.

Hoople, J. (1978, Fall). In Memorium: Jay Peterson. On Native Women: CASNP Bulletin, p. 2.

Indian-Eskimo Association of Canada (2016). Indian-Eskimo Association of Canada fonds, 1957-1970. Accession Number 95-006. Retrieved July 7, 2016 from Trent University Archives: trentu.ca/library/archives

MacBain, R. (2016). Their Home and Native Land. Robert MacBain. See pages xi-xii for MacBain’s explanation as to why he uses the term Indian in his book. One of the reasons is that the “32 Ojibways, Mohawks and Cree” who he interviewed for the book did not find the “word to be insulting, pejorative or offensive. They used it all the time.”

McCallum, I (1998). Part 2b – Human Heritage/First Nations: Thames River Watershed. Retrieved June 30, 2012 from Canadian Heritage Rivers System: thamesriver.on.ca

Munsee Delaware Nation. Retrieved December 11, 2016 from: munsee.ca

Oneida Nation of the Thames. Retrieved December 11, 2016 from: oneida.on.ca

Peterson, C.T. (ca. 1970). Peterson, Jessie Royce (Fleming) – “Jay Peterson.” London, Ontario. unpublished.

Peterson, J. (1975, March). Phase Five: Experiencing Equality [seminar, unpublished]. University of Western Ontario, Department of Occupational Therapy.

Peterson, L. (2003, May 10). Remembering Mom. London Free Press, p. F3.